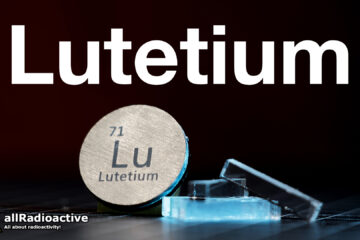

Exploring Naturally Radioactive Elements – Lutetium 176

Welcome back my fellow radiation nerds!

When we think of naturally occurring radioactive elements we mainly think of Uranium and Thorium and maybe sometimes Potassium. While those elements are the most common ones, there are many others that also have naturally radioactive isotopes. However, most of them have very long half-lives making them extremely hard to detect, especially without specialised equipment, but there are a few that can be measured with a sensitive Geiger Counter or Scintillation detector. One of them is Lutetium with its radioactive isotope of Lutetium 176.

If you enjoy this content make sure to subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss any of the upcoming uploads. Thanks and now back to the video!

The Discovery

Lutetium has been discovered independently by three scientists in the year 1907, a French scientist George Urbain, Austrian mineralogist Carl Auer von Welsbach, which you might also know as the inventor of Thoriated gas mantles, and American chemist Charles James. After years of dispute, George Urbain has been named by the scientific community as the discoverer of the new element and he named it Lutetium after Lutetia, the ancient Roman name for the city of Paris.

Properties of Lutetium

Lutetium is a rare earth element with an atomic number of 71. It is the last element in the Lanthanide series and it shares many of the chemical properties with other elements in the group. In nature, it has only 2 isotopes, a stable Lutetium 175 (97.4%) and a radioactive Lutetium 176 (2.60%).

Lutetium 176 undergoes a beta decay with an average energy of 182 keV, turning into Hafnium 176 with a half-life of 37.8 Billion (3.78e10) years, and in the process it also emits gamma rays at 88, 202 and 307 keV. What is Interesting about Lutetium 176 is that the both gamma rays of 202 and 307 keV are emitted in coincidence with each other, forming summing peak at 509keV

Uses of Lutetium

Today Lutetium doesn’t see much use due to its difficult production and very high costs but it can be found in some specialised fields. One of its main uses is in the production of scintillation crystals which are used in positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

It can also be found in some alloys like in the case of like LuAG where it improves the overall durability and heat resistance of the material.

And thanks to its long half-life, Lutetium 176 can be used for Lutetium-hafnium dating of meteorites.

My samples & their radioactivity

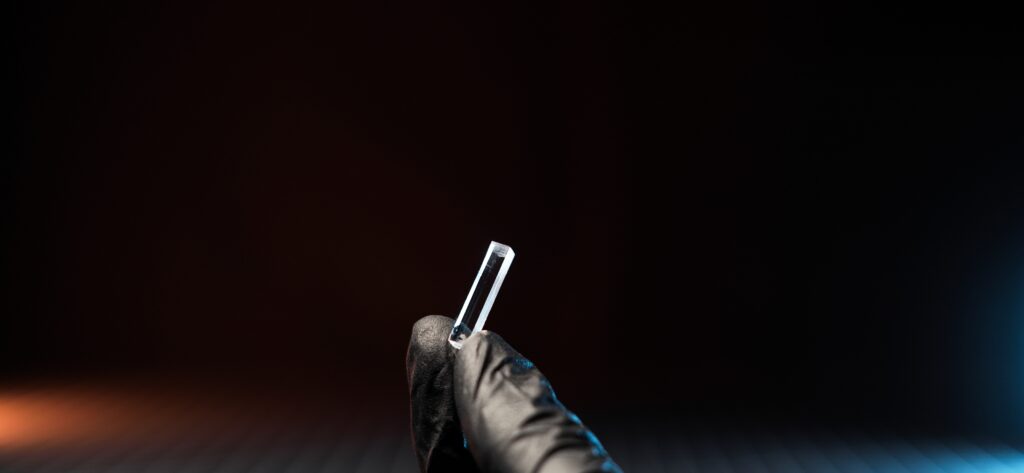

At the moment, I have two types of Lutetium samples. The first one is a form of LYSO scintillation crystals which I got from a friend of mine (thanks James!), I have linked his eBay store in the description below in case you want to grab one for yourself.

When measured with SE International Ranger which uses a LND7317 Pancake type tube, I got from a single crystal 73 CPM, only 30 CPM over the background radiation. When measured with my RAYSID I got an increase of 15 CPS in the activity which is more than enough to build a gamma spectrum, however a good lead castle to minimise background radiation is definitely a good idea.

As mentioned before, these crystals are used in positron emission tomography (PET) and when exposed to radiation they glow in a light blue colour.

My second sample is a metal coin made out of pure Lutetium metal which measures 24.26 mm x 1.75 mm and weighs about 8.43g, this means it contains around 0.218g of pure Lu176 that has activity of approximately ~432 Bq. Compared to the LYSO crystal, the activity is a bit higher and reads on my Ranger 160 CPM above background and 55 CPS on my RAYSID.

Since the coin is made of pure metal, it is much denser than the LYSO crystal and some of the activity gets self shielded which results in the readings being a big lower than expected.

Since I use it as my main Lu-176 source for gamma spectroscopy, I decided to put it in a 1″ plastic disk with a label stylised a bit after other professional calibration sources. While it might be a bit goofy or silly to some, I do enjoy a consistent look of my sources and I’m very happy with the results.

Isotope Lutetium 177

In nuclear medicine, a synthetic isotope of Lutetium, Lu-177 is used in targeted cancer therapy. It is produced by neutron irradiation of Lu176 and it decays through a beta emission into Hafnium 177 with a half-life of 6.65 days and it emits two gamma rays at 113 keV and 208 keV.

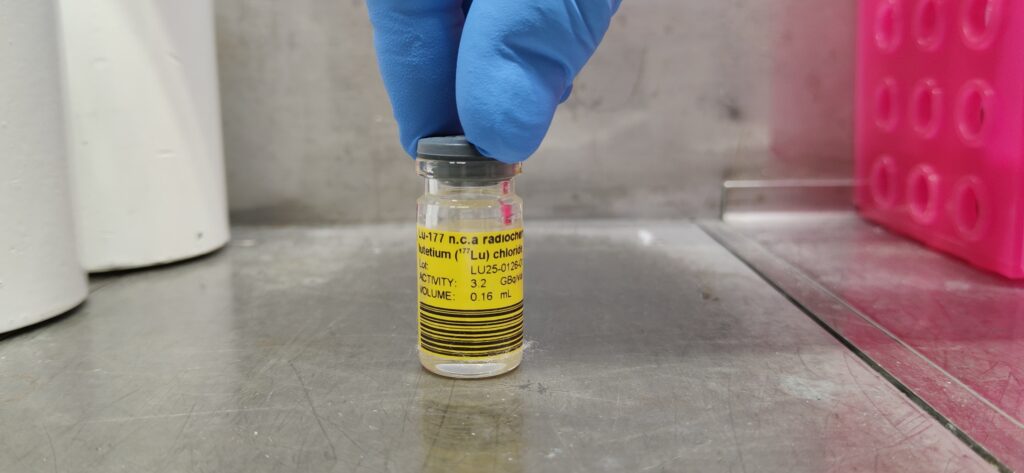

A good friend of mine works in a nuclear lab and recently they received a fresh batch of Lu177 for their experiments and he was kind enough to make some videos showcasing the samples, testing them against some of his meters and take a gamma spectrum of them. Big Thanks for the help!

Originally this vial contained 3.2GBq of Lu-177 in form of Lutetium Chloride solution, however most of it has been already removed and now there are only traces of Lu-177 left. Despite that, the vial still read pretty high on the RadEye B20 with over 60k CPM and registered 760uSv/h on the RAYSID.

Summary

Exploring the radioactivity and the history of Lutetium and its isotopes was definitely a great experience and I have learned a lot about it. I want to hear from you, did you know about the natural radioactivity of Lutetium and do you have any samples of it? What other radioactive elements should I cover next? Let me know in the comments below!

Thank you so much for reading this post, I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new! If yes, please make sure to subscribe to the email list so that you get notified when new posts are added. Also feel free to check out my Patron page where you can support the channel financially and get some additional exclusive content.

and remember, stay active!