Welcome back, my fellow radiation nerds! Today, we’re diving into the radioactivity and the geology of a very unique mineral called Radio-Barite.

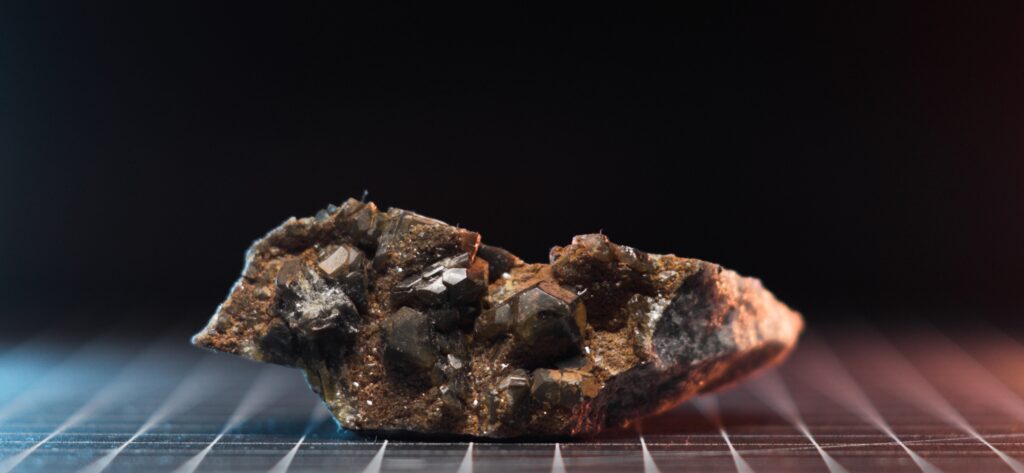

Radio-Barite is a variation of the Barite mineral, and, as the name suggests, it’s radioactive as it contains a small amounts of Radium-226. Since Radium is chemically very similar to Barium it can be easily incorporated into the Barite mineral structure during its formation, if it’s present in the surrounding environment, usually in trace amounts in groundwater or the surrounding uranium minerals. Its chemical formula is (Ba,Ra)SO₄, and its crystals usually have brownish colour and form an orthorhombic structure and score 3–3.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness.

What makes Radio-Barite particularly unique is that it contains radium without its parent isotopes such as Uranium, Thorium or Protactinium, however impurities can sometimes result in the presence of those elements in the mineral. Radium-226 has a half-life of 1,600 years, meaning that for pure Radio-Barite to exhibit detectable radioactivity, it must have formed within the past few thousand years.

Non-radioactive Barite is the primary source of element Barium, which is mainly used in natural gas and oil drilling to prevent blowouts. It’s also added in small amounts to many everyday items. If Radio-Barite is mined instead of non-radioactive Barite, contamination can occur since radium is very difficult to separate from Barium due to their chemical similarities. However, this is rare, as the ore is strictly measured to ensure it doesn’t exceed NORM (Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material) limits.

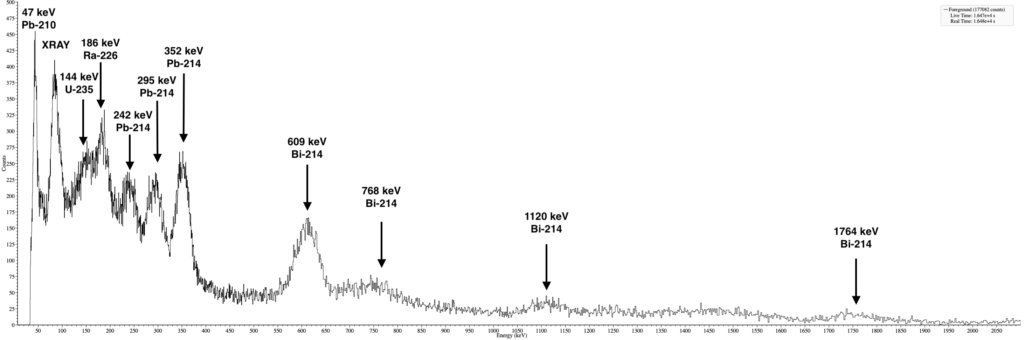

Gamma Spectrum and activity of my sample

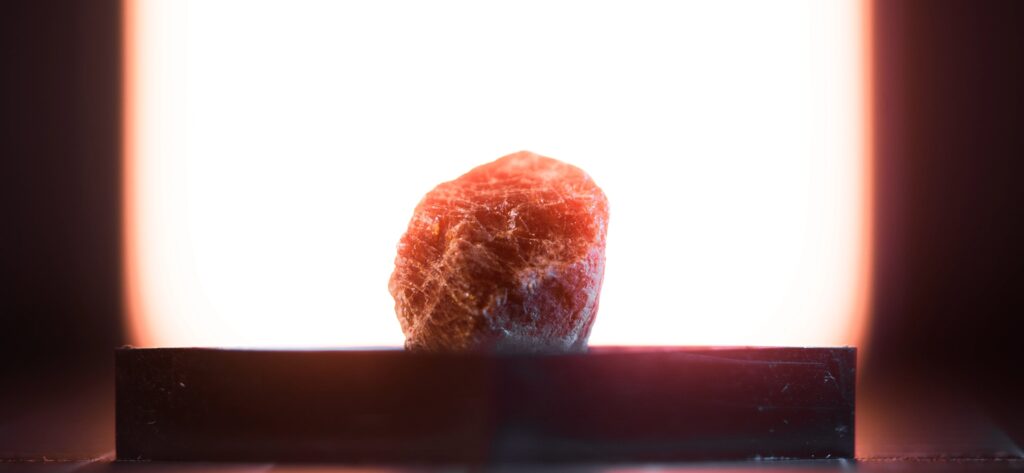

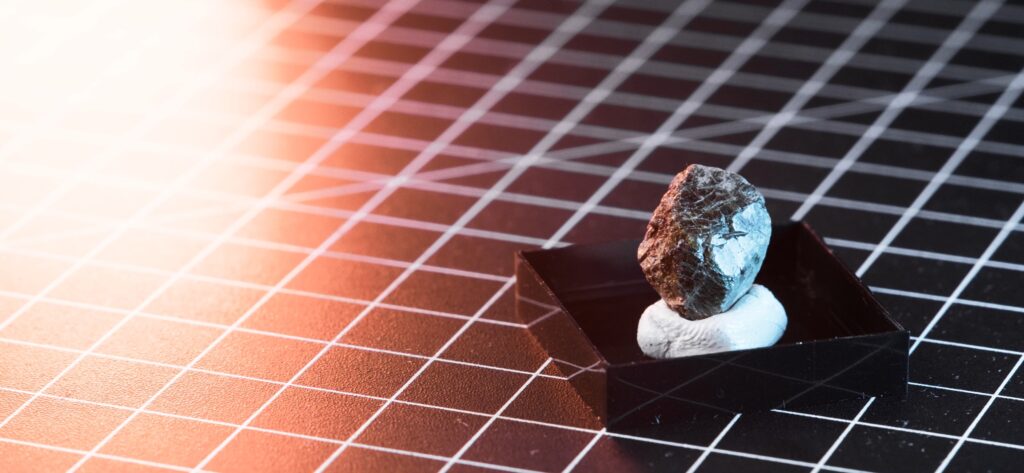

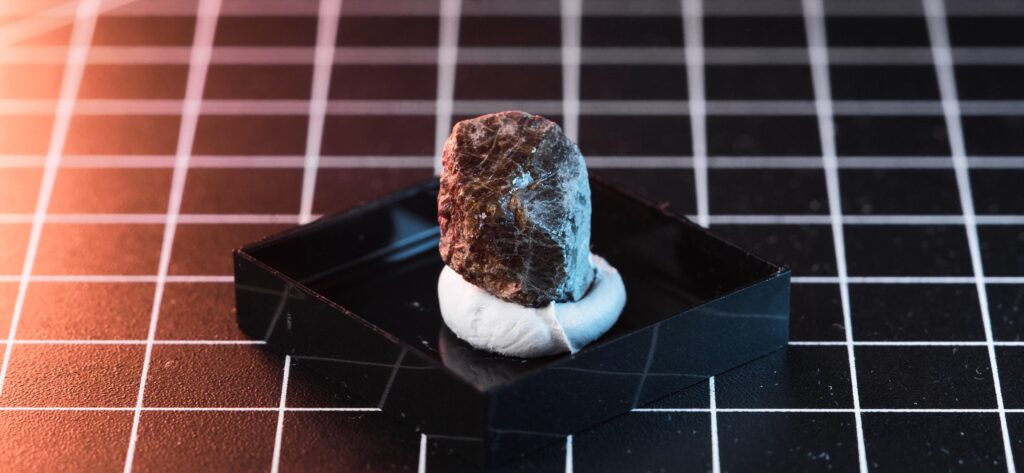

My sample of Radio-Barite comes from Jeníkov in the Czech Republic, a region known for its high-grade uranium deposits. The sample has beautiful, large, brown crystals, which do not fluoresce under black light and are formed on top of quartzite quarry matrix.

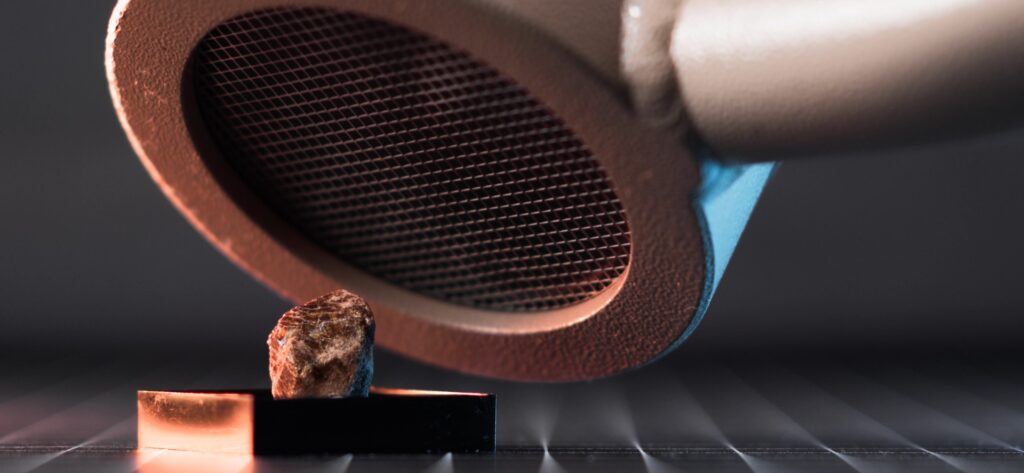

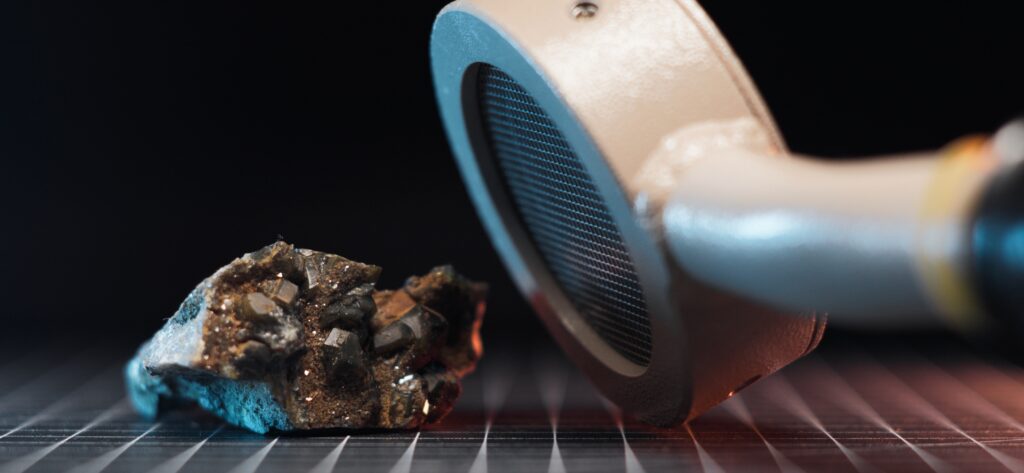

Even though Radio-Barite contains only trace amounts of radium, its radioactivity is detectable with most Geiger counters. My sample measures around 400 CPM on my Ludlum Model 3 with a 44-9 probe. The emitted gamma dose rate is rather low at approximately 0.12 µSv/h over background when measured with my RAYSID also at 1 cm distance.

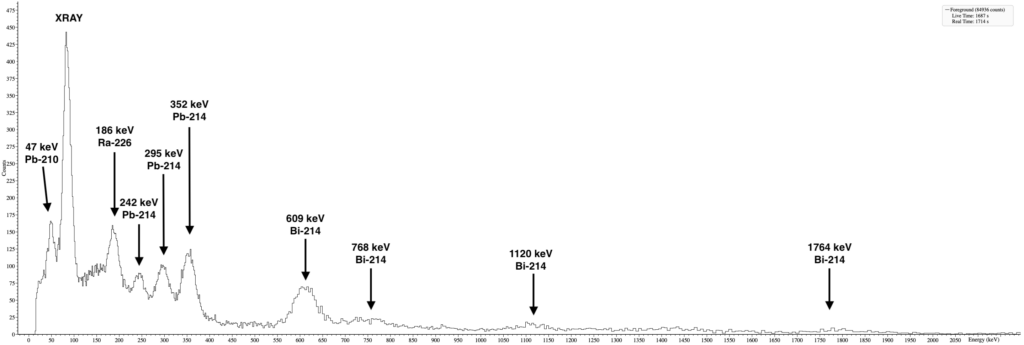

A quick gamma spectroscopy of my Radiobarite mineral revealed an interesting spectrum. I expected to see a clean Ra-226 spectrum but the peak at 144keV indicates the presence of Uranium. This is most likely due to impurities that were picked up by the mineral during its formation in a Uranium rich environment.

For comparison, here is a spectrum of pure Ra-226 from an old radium painted watch. While similar, the U235 peak at 144keV is missing which is distinctive feature between natural uranium and radium spectra.

A few final words

Exploring the geology and the radioactivity of my RadioBarite mineral sample was a lot of fun and I certainly learned a lot about it! I want to hear from you, did you know about the radioactive radio-barite before and do you have any samples of it? What other radioactive minerals should I cover in the future videos? Let me know in the comments below!

Thank you so much for reading this post, I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new! If yes, please make sure to subscribe to the email list so that you get notified when new posts are added. Also feel free to check out my Ko-Fi page where you can donate a nice cup of radioactive coffee and support my work financially.

and remember, stay active!