Welcome back my fellow radiation nerds! Today we will take a closer look at radioactive contamination inside of my lead pig container and try to identify the isotope behind it.

Lead pigs are lead containers used to store highly radioactive sources and shield their radiation to help minimise exposure. This one in particular originally came from one of the German nuclear power plants and it is made out of solid lead and weighs about 2kg. Although the container did not come with any radioactive sources, after unboxing the package, I noticed that the inside of the container emitted radioactivity and was most likely contaminated with some mysterious radioactive source.

This discovery was very exciting and I was very curious to find out what isotope was behind the contamination.

What are we dealing here with?

There plenty of different radioactive isotopes out there, some are natural such as Uranium and Thorium and their decay products, and some are man-made produced in nuclear reactors, in particle accelerators or during atomic tests.

In order to find out what isotope is behind the contamination, I need to narrow down my search and eliminate any isotopes that don’t match the characteristics and properties of the one inside the lead pig.

I’ll start by checking what type of radiation is being emitted from the container. First, I’m going take a measurement first without any shielding and then I’ll start introducing different materials to block out different types of radiation and compare the results. For this purpose I will use my Ludlum Model 3 with a 44-9 probe as it can easily detect alpha, beta and gamma radiation.

- Alpha particles can travel in air up to 5cm and can be easily stopped with a thicker piece of paper.

- Beta particles can travel up to half a meter in air and can go through low density materials but a piece of aluminium should be enough to block them.

- Gamma rays can travel very long distances and are the hardest to shield requiring very dense materials such as Lead or sometimes even Uranium.

From my first measurement without any shielding and I got a result of about 1000 CPM at 1cm distance from the lead pig. After placing a piece of paper between the probe and the container, the result remained unchanged. This meant that there are pretty much no alphas being emitted by the source.

Next, I’ve added a piece of aluminium and the readings dropped significantly, all the way back to background levels meaning that the source was a primarily a beta emitter and even if there was some gamma radiation, it was extremely low and not detectable by my meter.

Gamma Spectroscopy

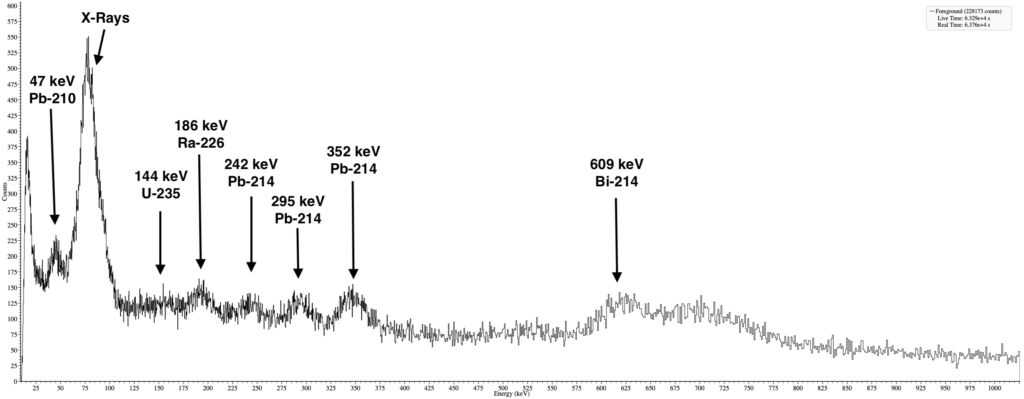

Although I haven’t detected any gamma radiation above background levels, I still decided to do a gamma spectroscopy with my RAYSID. Sometimes even trace amounts of gamma radiation are enough to build a good spectrum and identify different isotopes.

Inside my lead castle, the background activity is only 1.2 CPS when measured with my RAYSID. After placing the lead pig container inside, I got reading of 3.5 CPS and after collecting data for few hours, I managed to create a gamma spectrum of the lead pig.

The gamma spectroscopy revealed peaks that are characteristic for Uranium ore. I spoke with the previous owner and he did mention that he stored uranium ore inside so definitely there is a chance that a small piece broke off the mineral and is at the bottom of the container, however the amount of beta radiation compared to gamma could hint at another contaminant but unfortunately I don’t have the tools to properly check or identify it.

Conclusion

This is actually not the first time that I see a contaminated lab equipment. A friend of mine has a lead pig that is contaminated with radioactive Cs-137 as a result of a chemical spill inside of it.

I want to hear from you, did you ever find some contaminated lab gear and do you think the remains of Uranium ore are the only contamination inside of my lead pig or could there be some other radioactive isotope. I’m looking forward to hearing your suggestions and answers in the comments below.

Thank you so much for reading this post, I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new! If yes, please make sure to subscribe to the email list so that you get notified when new posts are added. Also feel free to check out my Ko-Fi page where you can donate a nice cup of radioactive coffee and support my work financially.

and remember, stay active!