History

On July 16th, 1945 the United States tested its first nuclear weapon at the Trinity test site located in the Nevada desert, New Mexico. The bomb tested there was called the Gadget and it was a prototype of a Plutonium implosion-type bomb, similar to the one which was dropped on Nagasaki (Fat-Man).

When the Gadget exploded, the intense heat caused the steel tower, as well as surrounding sand to melt and form what we now call Trinitite.

Today, it is illegal to take Trinitite from the test site but you can buy it from different sellers online, who have collected it before the ban.

Different types of Trinitite

Trinitite comes in three different colours. The most common is green, a little bit rarer is red which contains copper from the wiring inside of the Gadget and finally black, which is the rarest and it contains iron from the steel tower on which the Gadget was placed.

Trinitite has a very low activity. When put together, my samples measured at around 110 cpm with a Pancake probe.

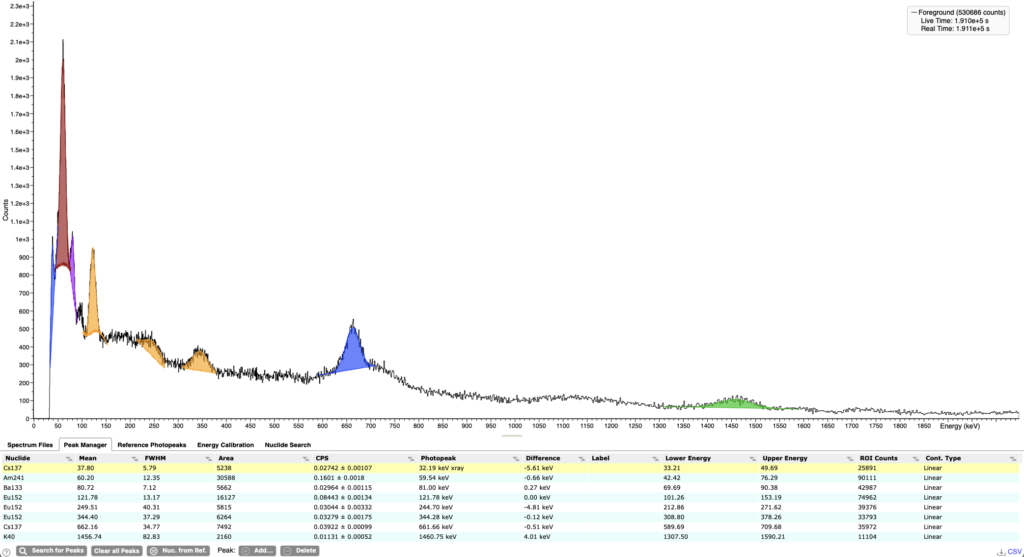

Fake trinitite & gamma spectroscopy of a real sample

Unfortunately, the rise in demand for Trinitite caused some scammers to start selling fake samples. They make them by mixing sand with radioactive isotopes such as 90Sr and then heating it to extreme temperatures. As a result, they create glass that is very similar in looks to Trinitite and even is slighly radioactive. In order to verify if the sample is real or not, it is best to do gamma spectroscopy of it. A spectrum of a real Trinitite should show the following isotopes 241Am (59 keV),133Ba (81 keV), 152Eu (123 keV, 245 keV, 344 keV), 137Cs (31 keV, 662 keV) and 60Co (1173 keV, 1332 keV).